Software Development in the Age of AI Coding Agents

When cost of code approaches zero, implementing intent and managing complexity become the job

«No AI was used in writing this article. Other than the obvious use of Gemini Nano Banana Pro for the images.»

It’s hard to make predictions, especially about a future that’s rapidly unfolding like science fiction in real life and feels surreal and palpable at the same time. But, that’s exactly what I’ll try to do in this article: predict the future of software development across multiple dimensions.

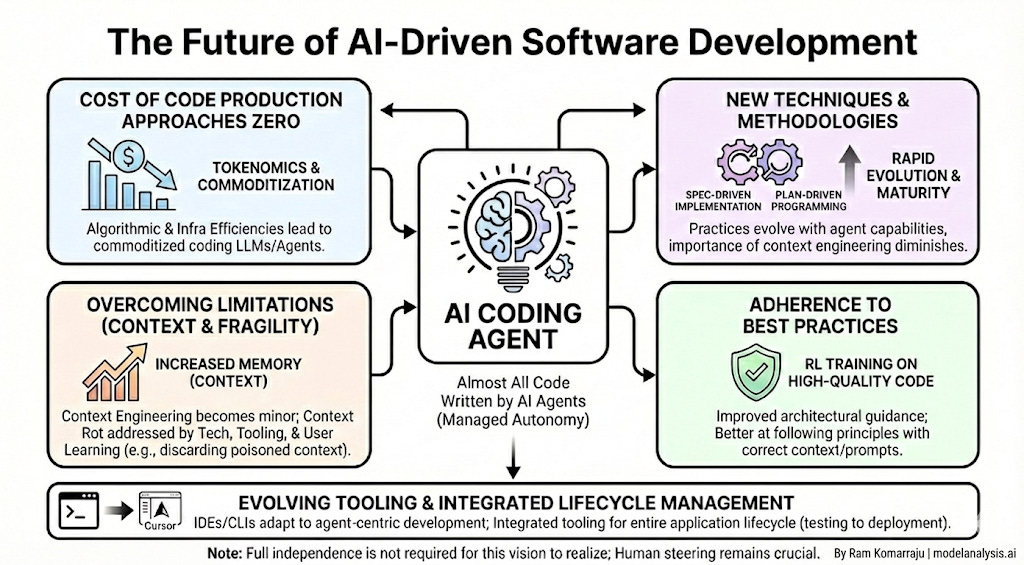

AI Coding Agents Will Continue to Get Better

As we stand at the cusp of 2026, I think we can confidently envision a future where almost all of the code will be written by AI coding agents. Here are a few supporting factors that will turn the vision into reality:

Cost of producing code will approach zero for all practical purposes. This is pure tokenomics at play. There’s little to distinguish between different leading models, and when coupled with the inevitable algorithmic and infra efficiencies, this can only lead to the eventual commoditization of the coding LLMs (and the agents on top of that).

The three major limitations that currently plague LLM-based coding agents will become only minor limitations over time:

The amount of memory (context) that LLMs can hold at a given time will increase over the next couple of years. So much so that it won’t be the major limitation that it is today. So, context engineering, much like prompt engineering from ‘23-24, will become a sidebar conversation within the next couple of years.

Context rot and fragility to prompting will be addressed at the underlying technology and surrounding tooling levels, as well as by users learning to use the coding agents more effectively. For example, we will learn to discard a poisoned context and move to a new context quickly, and configure system and tool prompts to extract the best performance.

LLMs will get better at following best practices and architectural principles. In my opinion, this is a matter of RL training on more and more examples of high quality code annotated with comments highlighting best practices. In other words, creating high quality code will get better assuming that correct context and prompts with architectural guidance are used.

We will develop new techniques and methodologies to use the AI coding agents effectively (e.g., spec driven implementation and plan driven programming). These practices will continue to evolve at a rapid pace as long as the coding agents continue to evolve in their capabilities, and will reach their maturity as coding agents will reach a mature state. For example, the importance of context engineering will diminish as context length increases, and coding agent developers would have learned how and what to include in the context efficiently. Similarly existing tooling for coding (e.g., IDEs or CLIs) will continue morph and adapt to this new paradigm. We see this transition already whereby IDEs and CLIs adapting their interfaces and tooling around agent-centric development. I predict that we will see integrated tooling that will enable users to manage the entire lifecycle of the application (from testing to deployment) from within a single application like Cursor.

Note that we don’t need coding agents to work completely independently for hours and days in order for these predictions to come true.

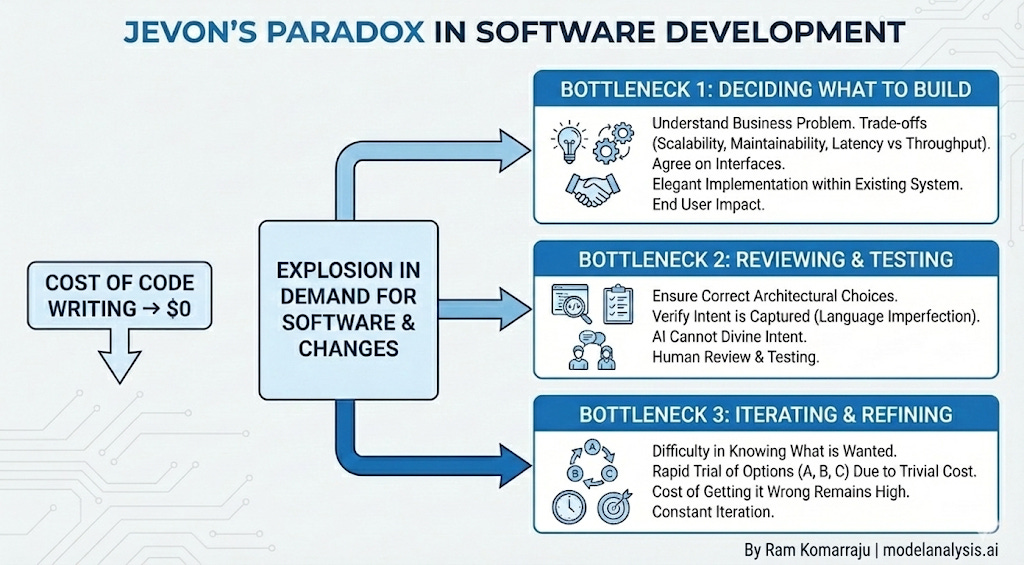

What are the likely broad implications for software development?

We’ll see Jevon’s Paradox in action. When cost of writing code approaches zero, there will be more demand than ever to write new software, and the bottlenecks move elsewhere:

Deciding what software to build or what changes to make to the existing software. There’s a tremendous amount of work done outside of coding. You need to understand the business problem. You need to understand the trade offs between scalability, maintainability, and latency vs throughput, and choose the options suitable for the context at hand. You need to agree on the interfaces with other teams. And then you find the way to implement it in an existing system in as elegant a way possible while keeping in mind the impact it might have on end users.

Reviewing and testing what’s been written. In ‘26 it might still be about ensuring that the correct architectural choices are made, but increasingly it would be about ensuring the intent is captured appropriately. Because language is an imperfect communication mechanism and even the best coding agent cannot divine the user’s intentions correctly all the time.

Iterate through what’s been written. Just because software can be produced easily doesn’t mean that can we can get to what we want very quickly. For one thing, it’s often very difficult to know what one wants, and getting things right requires iterations. So, we’ll likely try options A, B and C because of the cost of trying things is trivial, while the cost of getting it wrong remains high.

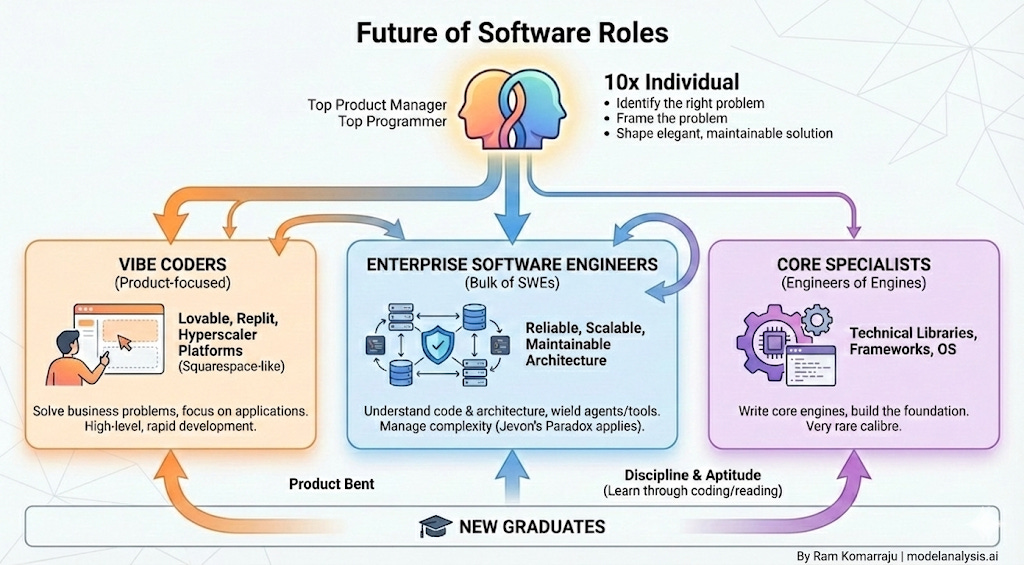

What does this mean for people/jobs?

There would be many hardcore vibe coders who just want to develop applications to solve the business problem at hand. These individuals will gravitate towards platforms like Lovable, Replit (and other offerings that hyperscalers like AWS are likely to provide). These are the Squarespace/Shopify-like platforms of the future.

Software engineers that understand code better, know architectural best practices and can wield the agents/tools to operate reliable, scalable, and maintainable enterprise software of the future. This forms the bulk of the current SWE space, and I predict that Jevon's paradox will hold here. The skills needed in this space will change, but the number of jobs won't reduce as demand grows in response even as the cost of code approaches zero.

A few specialists will remain writing core engines of the software world - those that develop technical libraries, frameworks, and operating systems, etc. There have been very few individuals of this calibre and the revolution in coding agents isn't going to change that.

New graduates will end up falling in one of the above three buckets. Those that have more of a product bent might end up landing in the first bucket. Those that have the discipline and aptitude to learn through actual coding (when an all-powerful coding agent is a tantalizing keystroke away) and reading technical books will be valuable and employable, joining the latter two categories.

A 10x individual of the future would be a combination of a top product manager and a top programmer of today. And just as today, they will be as rare to find. They will know how to:

identify the right problem to solve

frame the problem so that finding the solution becomes possible

shape that solution into an elegant, maintainable, and scalable design

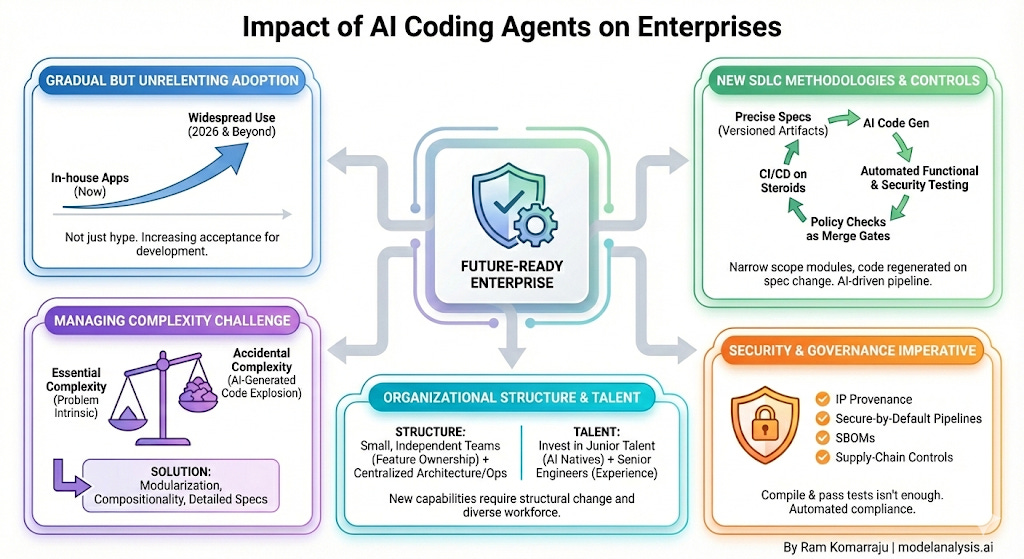

What does this mean for the enterprises?

Adoption would be gradual but unrelenting. I think by this point it must be clear to even the staunchest of the skeptics that coding agents aren’t just a part of the AI hype. Some of the enterprises have already started allowing coding agents for in-house application development, and this number will only increase in 2026 and beyond.

Managing the complexity of AI-generated code will be challenging. To borrow from Fred Brooks, software systems always had two different types of complexity - essential complexity (the intrinsic complexity of the problem we’re actually solving) and accidental complexity (all implementation details we’ve accumulated to ‘manage’ the application). Coding agents make the addition of accidental complexity incredibly easy. Imagine being able to write thousands of lines of code in a few hours where each thing ‘just about’ works. Modularization and compositionality along with detailed specs will become ever more important to address this problem.

New SDLC methodologies for this new paradigm will spring into place as organizations employ coding agents. One can imagine a method whereby each module’s scope is kept narrow and specified to great precision, and code is produced every time any part of the spec is changed. This is CI/CD on steroids, and wouldn’t be possible without implementing the necessary controls (see next paragraph).

It is not enough for agent-written code to compile and pass unit tests. Enterprises will likely need clear IP provenance for generated code and secure-by-default pipelines that produce SBOMs and enforce supply-chain controls. I expect new controls like specs treated as versioned artifacts, automated functional and security testing, and policy checks as merge gates. Of course, AI will play a key role throughout this pipeline.

Organizational structures will have to change to reflect the new capabilities and best practices. I can see a large number of small and independent teams with each of them owning a significant chunk of the functionality, but centralized teams for ensuring architectural cohesiveness and managing operational data.

It is a mistake for organizations to stop investing in junior talent. While senior engineers bring experience, new graduates are natives of the AI era. They adapt to new workflows more naturally and will ultimately become the backbone of the industry.

In conclusion, I wouldn’t worry if I were a software engineer today or aspiring to become one. As the barrier between intent and code thins, software engineers will be valued for steering AI with precision and keeping complexity under control.