The Great AI Code Transition

A Vision of What the Future of AI-Written Software Could Look Like

«Disclaimer and Notes: as is usually the case, there are many ways to present a narrative like this. I could’ve sliced the software into a completely different set of categories but I chose the set of categories that I thought would effectively illustrate the points I wanted to make. It should then be obvious that the percentages presented in the chart for various categories of code are meant to indicate a rough guess of what their relative sizes might be like. A more rigorous, data-based approach is needed to better ground this chart. It is often said that prediction, especially about the future, is hard. The biggest of my speculations is the extent to which AI generated disposable code would take over our interactions on edge devices. Finally, each of the points I wrote below can be expanded into an essay, and I might do that if there’s enough interest and response to this article.»

It is very clear as we enter 2026 that LLM-based AI coding agents have become powerful enough that more and more of code will be written using them. In fact, it is inevitable that in the not-so-distant future, almost all of the code will transition from being hand-crafted by humans to being written by these AI coding agents. This article looks at what a transition to such a future could look like.

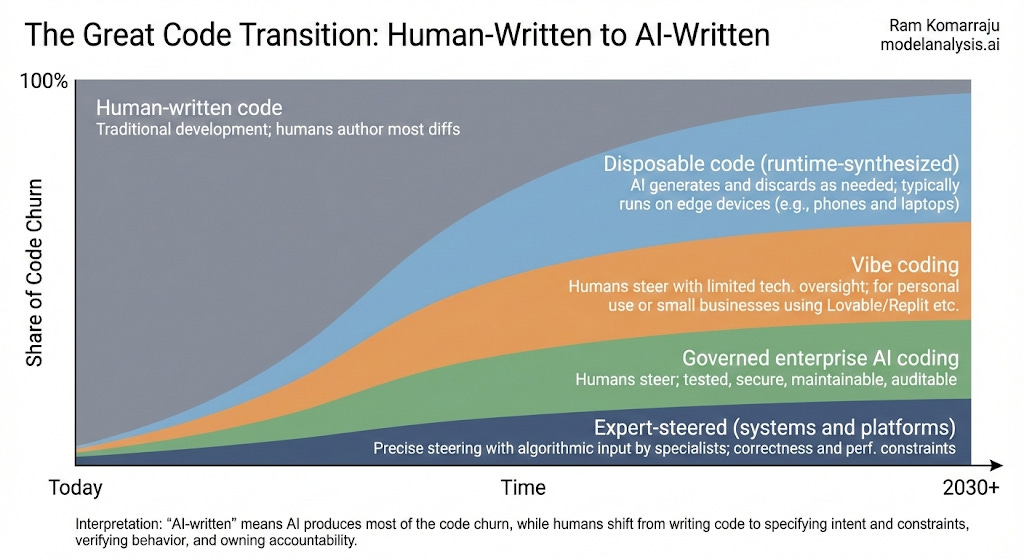

Let’s start off with a chart that compares at a high-level the present state of affairs with this future. The left-hand side of the chart presents the current state where almost all the code is written by humans (I know, I know, some of the leading tech companies and start ups might have been aggressively switching to coding agents already, but by and large the vast majority of places are still using humans to write the code). As we shift right along the X-axis, you can see more and more of the code being written by AI.

Here are some key observations about each of the four layers that will comprise the AI-written software:

How fast disposable software emerges on edge devices depends not only on model capability but also on privacy, latency, cost, power constraints, and offline reliability. Many consumer experiences may route through cloud inference to access stronger models, while privacy needs and regulatory requirements will push more on-device inference even if those small models are weaker. This will likely create a practical split in user experience, where the best functionality would be available to users that can afford to pay for better connectivity, newer hardware, and premium inference.

Platforms that enable sophisticated “vibe-coded” small business apps and sites will expand quickly. Users will focus on the business value proposition and user experience, while relying on the platform for scaffolding that provides security, payments, observability, data storage and compliance. This reduces the need for deep technical knowledge and extensive testing at small scale while increasing dependence on platform guardrails and concentrates risk in platform providers.

Large enterprises outside big tech will take longer to reach a fully AI-written software stack, maybe a decade or more, because the bottleneck is not capability but liability, controls, and regulations. They will need new SDLC and operating models that make AI-assisted changes auditable, reproducible, testable, and attributable, with clear responsibility when something breaks. The transition will be uneven: experiments and greenfield products will move quickly, while core systems of record and regulated workflows will lag. Organizationally, some middle layers of coordination shrink or change shape, and effort shifts toward governance, verification, security, reliability engineering, and incident response.

For systems and platforms, AI will write much of the code churn, but expert steering remains essential because correctness, performance, and security constraints are unforgiving. Specialists will focus less on manual implementation and more on precise specifications, choosing/designing the correct algorithms, and rigorous verification.

The next four points will focus on what this means from socio-economic and legacy system impact perspectives:

Many software builders who take pride and identity from craftsmanship will find the transition emotionally and professionally difficult as the work shifts from writing code to defining intent, setting constraints, verifying behavior, and owning outcomes. The people most likely to prosper are those with strong product judgment, clear vision, enough technical literacy to reason about tradeoffs, and the ability to communicate precise techno-functional requirements to coding agents. Deep specialists will still matter, especially in systems with high-performance, industrial-grade security, and safety-critical needs, either hand-crafting core components or steering agents with high precision. Status and fulfillment will increasingly come from accountability, reliability, and impact rather than elegance of implementation.

Entry-level coding jobs and many mid-skill implementation roles may shrink as AI can easily write simple code that would historically have been written by junior coders. It’d be interesting to see how the junior coders will be able to learn to become good coders in the age of AI coding assistants. At the same time, more people will be able to build sophisticated functionality without formal training broadening participation.

As to how AI functionality itself will be integrated into software, I’m expecting that two competing product visions will coexist for a while. One is special-purpose applications with AI embedded, optimized for functionality, precision, and performance. The other is a general-purpose AI layer that generates tailored interfaces and orchestrates specialized modules and systems on demand. If the general-purpose layer becomes the dominant interface, it challenges traditional suites like Microsoft Office by demoting Word and Excel to the back-end while elevating agent-driven interfaces to the top.

Finally, if something like AGI emerges, the technical need for human steering could drop further, but human oversight and accountability may still be required for legitimacy. I’m assuming (for humanity’s sake!) that ownership and liability will ultimately remain in human hands.

That concludes this short essay. There’s more that I can write on this topic, but this is all I could write in the time I’d allotted to myself. Let me know your thoughts, and thank you for reading all the way to the end :)

I saw this myself while building my personal project. AI helped a lot at the start with boilerplate and APIs, but once the codebase became big, it couldn’t keep the overall structure right. The code looked fine in parts, but didn’t work well as a system.

That’s when I realised humans still need to own architecture, data models, and core decisions. AI is great for speed, but not yet for maintaining a growing, long-term codebase.